1/11/2022: Intro and Testing, Coverage, and Linting

See: Chris’ Handy Testing Hints for some handy hints.

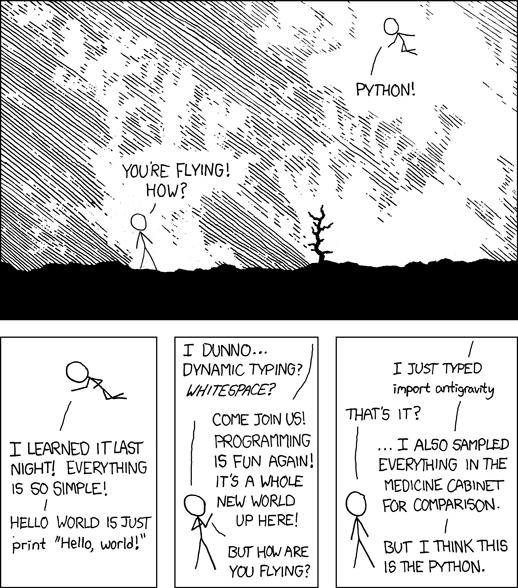

In which you are introduced to this class and your instructors, and continue your relationship with your now best friend, Python.

The goal of this lesson is get us all familiar with each other, the class, and all the tools and systems we’ll need to conduct the class. As this is the second in the series, that shoulnd’ttake too long, so we’ll get into Topic 1: Unit Testing!

Who are we?

Introduction to your instructors:

Chris

Luis

Who are you?

Despite the common myth of the lone programmer, most software development is a collaborative activity. As such, we encourage students in this class to work together whenever possible.

You all have been working together for some time already, but we instructors don’t know you yet. And particularly since this is an entirely online class – maybe it’s a good idea for you to reintroduce yourselves to each other as well.

So we’ll go around the Zoom and introduce ourselves:

Tell us a tiny bit about yourself:

Name

Why did you want to learn Python?

What’s one cool thing you learned about python last quarter?

Or one thing you really want to learn this quarter?

Is there anything from last quarter that you are confused about that you want us to clarify?

What is your gitHub handle?

Introduction to This Class

As before, the overall class is managed in Canvas. You should all be familiar with that now.

Is everyone “hooked up” to the Canvas instance for this class?

NOTE: I’m not a big Canvas fan: it’s where to go to find the readings and videos, get the links to the assignments and get on the Zoom, etc, but much of our interaction will be via MS Teams and programming tools, like gitHub, rather than Canvas.

NOTE: It’s UW policy that your assignments are uploaded to Canvas (as a zip file), so that there is a record of your work. But Luis and I will look exclusively at your PRs in gitHub Classroom to review your work. So do be sure to put a link in to the PR when you are ready for us to review.

Due dates: You assignments are all due before the next class sessions (i.e. Tuesday at 6:00 pm) – but we do encourage you to turn them in earlier, so we have time to review before the next class.

In any case – come to the next class prepared with questions, if you have them.

Class Structure

How will we spend this three hour sessions each week?

We will be using a variation of a “flipped classroom” for this class.

Class time will be spent primarily coding and addressing questions:

Still some lecture – as little as possible

Lots of demos

Working on the Exercises: - On your own, with us to help - In small groups (breakout groups on Zoom) - Instructor led.

This means that you are expected to complete the reading (and video watching) before each class. That way, we don’t have to take class time introducing the basic material and can focus on questions and applying what you’ve read about.

Interrupt us with questions – please!

Luis and I will be monitoring Zoom chat – but it’s easy to miss – so feel free to speak up!

(Some of the best learning prompted by questions)

NOTE: I will try to take a break about once and hour. But I tend to get “in the zone”, so may forget. Please feel free to remind me if you need a break!

Homework:

Homework will be reading, videos, and links to external materials – videos, blog posts, etc.

Exercises will often be started in class – but you will finish them on your own at home (and you will need time to do that!)

You are adults – it’s up to you to do the homework. But if you don’t code, you won’t learn to code. And we can’t give you a certificate if you haven’t demonstrated that you’ve done the work.

To submit your work, we will continue to use gitHub Classroom.

Communication

MS Teams:

We will use MS Teams to communicate – it’s a good way for us to communicate as a group, rather than more directly as individuals.

Most of you should already be members (with your uw email), but if not, I think you can go to that link and request to join.

Anything Python related is fair game. Questions and discussion about the assignments are encouraged.

We highly encourage you to work together. You will learn at a much deeper level if you work together, and it gets you ready to collaborate with colleagues.

I will also send occasional email out to the whole class – make sure I have the email address you want me to use. (I’ve got your uw email addresses now).

You can also send email directly to your instructors:

Chris: PythonCHB@gmail.com

Luis: ldconejo@uw.edu

Office Hours

We will generally will hold two “office hours” sessions on Zoom each week.

Please feel free to attend even if you do not have a specific question. It is an opportunity to work with the instructors and fellow students, and learn from each other.

What are good times for you?

New Expectations

Evaluation of your work

In the previous class, the focus was on getting the basics of Python down.

Getting the code to do what you want it to do

You were introduced to many of the concepts of good software development practices:

Code style / linting

Unit testing / TDD

Error handling

Well thought out code structure

Documenting the code

In this class, we will be emphasizing these ideas. The assignments will evaluated with all this in mind. In short, your code will be expected to:

Work correctly

Be PEP 8 compliant

Have complete Unit Tests (100% coverage)

Be documented (i.e. docstrings on functions / classes)

And now, some real work:

git / gitHub Classroom

You used gitHub classroom last quarter, so this should all be familiar.

SOMETHING NEW

The gitHub classroom for this class has been set up using a new UW organization. In order to ensure a bit more privacy for students, you need to have a gitHub account that is “hooked up” to a uw.edu email address. If your gitHub account is already set up with your uw.edu email address then you are all set.

But if it wasn’t, you have two options:

Create a new gitHub account, using your

uw.eduemail address – all good.You can add your

uw.eduemail address to your existing gitHub account – I think that’s the way to go.

Let’s do that now.

If you are not sure – then try to accept the first assignment, and

Once done, we can get the first assignment going:

Accepting the first assignment

Clone the assignment repo onto your machine.

Adding a file (

test_main.py)Commit your changes

Push your changes to gitHub.

For a reminder: (plus there’s a summary in Canvas):

https://uwpce-pythoncert.github.io/ProgrammingInPython/topics/01-setting_up/github_classroom.html

gitHub actions

SOMETHING ELSE NEW

gitHub has what’s known as a CI/CD (Continuous Integration / Continuous Deployment) system called “Actions”. This is a very complex topic that’s part of development operations (“devops”), which we are not getting into in this class. But in short:

gitHub actions are a way to run any process you like whenever the repository changes (you push code). This can be:

Building the code

Linting the code

Running the tests

Packaging up the code

Deploying the application

The list goes on and on ….

The gitHub classroom assignments for this class have been set up to run gitHub actions to do three things:

You probably haven’t completed the reading for the first week yet, but this is talked about there :-)

“lint” the code – run PyLint on the code to check for conformance with PEP 8

Run pytest – making sure all of them pass

Run “coverage” on your tests – to make sure that your tests are testing all of your code

If any of these three processes fails or is incomplete, then the “action” will fail, and gitHub will send you an email saying so.

NOTE:

“Failing the CI” does not mean that you have failed the assignment – but in order to get full credit, all these checks should pass.

NOTE 2:

These checks DO NOT CHECK IF YOUR CODE WORKS CORRECTLY It only means your code meets the standards for style and testing. Whether it does the job is up to you to ensure!

Finally: These results should not be a surprise – you should be doing these checks on your own before pushing to gitHub anyway.

This process mirrors real development practices – often there are policies that all code must “pass the CI” before it is merged into the production branch.

You should have seen your first CI failure when you created the assignment repo – which makes sense, you haven’t written the code yet, of course it fails!

Some notes about git

Now that we’ve done that, a few thoughts on git:

Have you got the gitHub classroom “flow” down?

Do you have any conceptual Questions?

Should I go over these notes?

git is very flexible, and does not lose data easily. However, it is much harder to undo things than it is to make changes. So you will be happier if you take some extra care to not commit changes that you don’t want. Some hints:

Always do a

git statusbefore you commit – make sure that the stuff you are going to commit is what you want!note that if you do

git commitit will only commit those files listed under “staged for commit”. But if you dogit commit -a(-a for all) then it will commit everything modified, i.e. “Changes not staged for commit:”.

Note in the status report:

$ git status

On branch main

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/main'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git checkout -- <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: notes_for_class/source/lesson02.rst

...

It even tells you want to do: use git add to stage particular files, or git checkout to revert a file back to its state as of the last commit. It doesn’t mention git commit -a, but that will commit everything that is “not staged for commit”.

If you are careful before the commit stage, then you won’t have to “roll back” changes very often.

But if you do:

There are other nifty hints on that page, if you get stuck.

Unit Testing

And now the actual assignment!

The first week is about Unit Testing and TDD. You were introduced to these concepts in the previous class, but we are now taking it up a notch. In particular:

How to use the

unittesttesting frameworkFixtures

Mocking

Code Coverage

You may find that much of the material in the readings / videos for this week are review – but review is a good thing !

Unit Testing Terminology

Unit Testing is a concept:

“a software testing method by which individual units of source code are tested to determine whether they are fit for use.”

Unit testing can be done in any language with any number of testing frameworks and test runners, including roll-your-own asserts in an if __name__ == "__main__": block.

A test framework is a collection of utilities that aid in writing unit tests.

A test runner is a utility that makes it easy to run unit tests, including reporting the results, etc.

test coverage is a measure of how much of the code under test is actually used when the suite of unit tests is run. Note that less than 100% coverage means the tests are incomplete. But even with 100% coverage, there may be many possibilities that have not been tested.

Test Driven Development (TDD): is “a software development process relying on software requirements being converted to test cases before software is fully developed”.

In short: write the tests before the code.

It can feel pretty awkward at first: After all, we are thinking about how to make the code work – that’s what we want to focus on. But trust me: it really does lead to cleaner, more robust code. And if you follow TDD, 100% coverage is almost guaranteed.

These are all concepts that are independent of the tools.

Python Unit Testing Tools

``unittest`` is a unit testing framework that is delivered as part of the Python standard library. It is used by cPython itself, as well as a number of major packages, e.g. Django.

``pytest`` is both a test runner and a unit testing framework. It can be used to run unittest tests, as well as the simpler tests based on the pytest test framework.

``coverage`` is a python package that helps you determine the coverage of a set of unit tests. It can be run by itself, or along with pytest, via pytest-cov.

Unit testing for this class

As unittest is part of the standard library, every Python developer should be familiar with it.

So this week’s exercise should be completed using the unittest framework.

For the rest of the class, you are free to use either unittest or pytest tests – whichever you find most productive.

But in either case, we expect you to follow TDD and have comprehensive test coverage

Any thoughts / questions about Unit Testing before we jump in?

unittest in practice

Usually, you will have completed all the reading / videos before class. So we’d be ready to jump right in to the Exercises.

But since you all should be familiar with testing already,let’s jump right in anyway!

Handy references for unittest:

The official docs:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/unittest.html

A cheat sheet for the asserts:

https://kapeli.com/cheat_sheets/Python_unittest_Assertions.docset/Contents/Resources/Documents/index

A complete TestCase:

unittest is a class-based system for structuring tests. Each actual test is a method of a subclass of unitest.TestCase.

(like pytest, the methods should be named test_something)

What does TestCase provide?

A set of “assert” methods for testing various things

optionally, “fixtures”, with

setUp()andtearDown()methods.

A simple test case (see code in class repo: Examples/Lesson01):

import unittest

class TestListSorting(unittest.TestCase):

sorted_list = [1, 3, 5, 6]

# sample_list = [5, 1, 6, 3]

def setUp(self):

self.sample_list = [5, 1, 6, 3]

def tearDown(self):

pass

def test_sort(self):

self.assertNotEqual(self.sample_list, self.sorted_list)

self.assertNotEqual(self.sample_list, self.sorted_list[::-1])

self.sample_list.sort()

self.assertEqual(self.sample_list, self.sorted_list)

def test_reverse_sort(self):

self.sample_list.sort(reverse=True)

self.assertEqual(self.sample_list, self.sorted_list[::-1])

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

How do you run these?

With unittest directly:

python test_simple.py

With pytest:

pytest test_simple.py

Personally, I like pytest as a test runner – even if we’re using unittest tests.

Let’s try that out, and then play around with it.

Chris’ Unit Testing Hints

Make sure that a new test fails at least once – it’s the only way to assure that (a) the test is being run, and (b) that it actually tests something –hopefully what you want it to test!

While you are debugging the code (or the tests) it sometimes helpful to force a failure:

assert False. That way pytest will not swallow any output from print statements, etc.If you have a lot of tests, and are only working on one, you can sub-select with pytest.

One file: simply pass in the filename:

pytest test_simple.py

One test is a file: pass (part of) the name of the test with the -k flag:

pytest -k reverse_sort test_simple.py

Note: you can pass in an expression for fancier selection. See the pytest docs.

Running pylint

First make sure you’ve got it installed:

pip install pylint

Then it’s pretty simple to run:

pylint test_simple.py

Assignment 01:

Now that we’ve got that down – time to work on the assignment!

Let’s go to your gitHub classroom repo.

Lesson 1 Cheat Sheet:

See: Chris’ Handy Testing Hints for some handy hints on testing.

TL;DR

To install what you need:

pip install pytest-cov

(that will bring in pytest and coverage in one shot)

To lint your code:

pylint *.py

To run the tests:

pytest

(you should be doing this VERY often as you work on your code!)

To run the tests, and coverage:

pytest --cov

To run the tests, and get a nifty html coverage report:

pytest --cov --cov-report=html

For more detail

In lesson 1, we (re)introduced a set of good software development practices:

Unit testing

Test Driven Development

Test Coverage

Code Linting

Recall that these are best practices –there are a number of tools you can use to do these things. What follows is a quick cheat sheet for how to use the tools we recommend.

Testing Framework

For this lesson, you are expected to use the unittest test framework. Here are a couple handy references:

The official docs:

https://docs.python.org/3/library/unittest.html

A cheat sheet for the asserts:

https://kapeli.com/cheat_sheets/Python_unittest_Assertions.docset/Contents/Resources/Documents/index

Keep in mind that after this lesson, you are free to use unittest, or pytest directly, or a combination of the two.

Here are the pytest docs:

The getting started section is pretty handy for the basics.

Test Runner

unittest test runner

You can use either the built in unittest test runner:

Running the test file directly:

It must have this __name__ block:

if __name__ == "__main__":

unittest.main()

Then you can run it directly:

python test_main.py

Running it from unittest (this supports multipel files, etc)

python -m unittest test_main.py

pytest test runner

NOTE: If you haven’t already:

pip install pytest

pytest can run its own tests, as well as unittest tests. It will automatically look for files that look like tests (e.g. start with test_). It will then look in those files for functions and classes that look like tests, and run them. That makes it very easy to run:

pytest

That’s it! It will recursively scan for files and directories that look like tests, and run them all. If you want to run just one or two test files, you can pass them to pytest:

pytest test_main.py

If you want to run only a few tests in a test file, you can use the -k flag:

pytest -k users test_main.py

will run only the tests with “users” as part of the test name.

Test Coverage

Test coverage can be provided by the coverage tool.

https://coverage.readthedocs.io/

Make sure you have it:

pip install coverage

Coverage works as a two-step process: first you run it to compute the coverage, then you use it to make a nifty report.

Running coverage:

coverage run -m unittest test_main.py

or

coverage run -m pytest test_main.py

To see the results:

coverage report

To get a nifty html report:

coverage html

Then point your browser at the htmlcov/index.html that is created.

Try it out – it’s very cool! It provides a visual line by line report.

pytest-cov

The pytest-cov package integrates coverage with pytest, making it a touch easier to run.

https://pytest-cov.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

pip install pytest-cov

pytest --cov

If you want only one or a couple files checked:

pytest --cov=main --cov=users test_main.py

(note that you don’t use the .py extension – it’s the name of the python module, not the)

Finally, you can run the tests, compute the coverage, and produce the nifty html report in one command:

pytest --cov --cov-report=html

This is a nice way to go.

Linting

There are a number of linting tools out there: pylint, flake8, pycodestyle, and more.

For this class, we are going to primarily use pylint – it’s a solid option.

pip install pylint

To lint an individual file:

pylint main.py

To lint all the python code in a dir:

pylint *.py

Pretty simple, eh?

A linter in your editor / IDE.

It REALLY helps if your editor yells at you for style issues as you write your code.

Otherwise, you’ll find a LOT of errors when you finally get around to running pylint!

pylint can be configured to work with most common Python editors – configure yours now!

https://pylint.pycqa.org/en/latest/user_guide/ide-integration.html

The gitHub CI

As mentioned in class, the gitHub CI is configured to run tests, coverage, and lint your code. We wrote the CI script to be as generic as possible, as we can’t know in advance exactly how you might structure your code. If you want to replicate what will happen in the CI, you’ll need to run these commands:

pylint *.py

pytest ./

pytest --cov --cov-fail-under=100 ./

Note that this is running the tests twice, once with, and once without, coverage –

we did that so you’d get a separate failure for coverage than for tests failing.

But if you run that last command, you will get both.

(you can probably omit the cov-fail-under=100, that’s only for the CI).